The Japanese Nursery Industry in the Bay Area

Planting Roots

The flower industry in the San Francisco Bay Area began during the 1850s Gold Rush, when successful prospectors and merchants found themselves with an excess of wealth–and were eager to spend it. Soon, flowers were no longer luxury items but expected adornments in hotels and restaurants. They also played an important part in the celebration of births and weddings, as well as at funerals, and other rituals that spanned all classes of people.

It was during the rise of flower popularity that the Domoto brothers first arrived in California from Japan. Takanoshin Domoto landed in San Francisco on 18 November 1884. Three of his brothers soon followed and by 1885 they were growing chrysanthemums and carnations at their small nursery in Oakland. The Domotos are credited as the first in Northern California to commercially produce a variety of garden plants such as camellias, wisterias, azaleas, and lily bulbs imported from Japan. Their business thrived and in 1892 the brothers bought two acres in Oakland’s Melrose district on Central Avenue (now 55th) and East 14th Street. They may have been the first Japanese to own land in the United States. In response to local demand the innovative Domotos grew their business, adding several new flowers to their production line and buying more land next door.

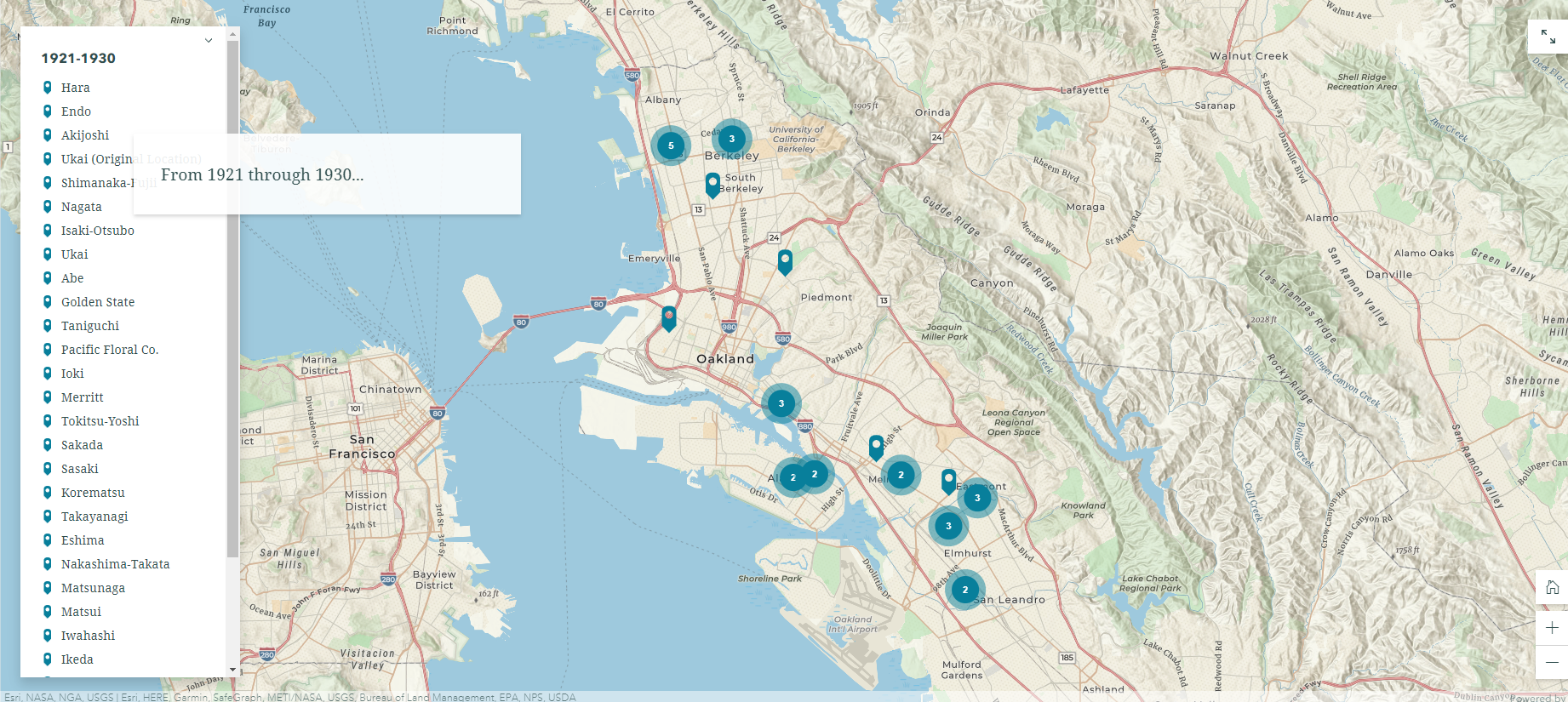

The Domoto Nursery’s success was fueled by the growing popularity of ornamental plants and cut flowers in the Bay Area. In 1902 the Domoto Nursery expanded again, this time to a larger site on Krause Street in the Oakland foothills. The family’s new 40-acre site was the first large scale Japanese nursery in the U.S. The Domoto brothers’ success was encouraging to those they knew in Japan. The brothers actively recruited workers from their home prefecture of Wakayama and many friends and relatives eventually came to America to learn the business and follow in their countrymen’s successful footsteps. The large number of Japanese trained by the nursery eventually earned it the nickname, “Domoto College”. The brothers encouraged their trainees to start their own businesses, creating a concentration of Japanese nurseries in Oakland and the greater East Bay. Eventually most large Bay Area nurseries were owned and operated by nurserymen trained at Domoto College.

The nurseries were concentrated in two areas: the East Bay (Oakland, Berkeley, Richmond and eventually San Leandro, San Lorenzo, and Hayward) and the San Francisco peninsula, including San Mateo, Belmont, Redwood City, and Mountain View. An important reason for the success of nurseries in the East Bay was its ideal climate that provided cool breezes and fog in the mornings partnered with afternoon warmth and sunshine.

Property values were also lower in the East Bay than in San Francisco. Japanese immigrants were able to buy small plots of land on city outskirts for relatively low prices. Transportation was also relatively well developed in the East Bay so the growers located their nurseries in the affordable suburbs along railroad lines and the Key System which provided streetcars, rail lines and buses for Oakland, Berkeley, Alameda, Richmond, El Cerrito, Emeryville, Albany, Piedmont, and San Leandro. Every morning the growers would transport their flowers from their East Bay nurseries to San Francisco-bound ferries. In the city they would sell to retailers. At first the growers sold outdoors. A spot on the corner of Kearny and Market streets in San Francisco gradually became an unofficial gathering place for growers and retailers to do business.

In 1906 the Japanese flower growers organized the California Flower Growers Association with 42 charter members. Chinese and Italians were also important players in the Bay Area cut flower industry. Italian flower growers organized the San Francisco Fern Growers Association and at first were heavily involved in selling greenery used in bouquets. Eventually these growers expanded their businesses to include a variety of cut flowers and what had been the Fern Growers Association became the San Francisco Flower Growers Association. Chinese flower growers entered the industry in the 1890s. Unable to find work because of exclusionary laws, Chinese started nurseries on the peninsula where they grew pompons, heather, hydrangeas and sweetpeas and established the Peninsula Flower Growers Association.

The initial objective of the California Flower Growers Association was to establish an indoor market site. After three years of searching a building was finally found at 31 Lick Place in an alley between Kearny and Montgomery and Sutter and Post streets. The market served as a central location for Japanese, Italian, and Chinese flower growers to sell their products. The flower market moved to a larger location at 5th and Howard streets in downtown San Francisco in 1924. It eventually expanded to an even bigger site at 6th and Brannan streets where it still operates today as the San Francisco Flower Mart.

Overcoming Obstacles

Because of their role in rituals of celebration as well as tragedy, flowers are essential during all seasons of life. The 1906 earthquake was one of many events in history that the flower industry survived. World War I and the influenza epidemic that immediately followed saw a spike in flower sales and prices. Japanese flower growers enjoyed continued success in the post-war years, producing 70 percent of the major greenhouse flowers and chrysanthemums in Northern California in 1929. Japanese nurseries were at the height of their success when the stock market crashed that year on October 28.

Along with the rest of the nation’s economy, the flower industry struggled with recovery in the 1930s as business slowly improved. The completion of the Bay Bridge in 1936 made it easier for the East Bay growers to sell their flowers in San Francisco. Business was steadily improving when, in December of 1941, the Japanese flower growers along with all people of Japanese descent on the West Coast had their lives turned upside down by the aftermath of the bombing of Pearl Harbor. In the months that followed, the nation was taken over by panic that bordered on hysteria which resulted in President Roosevelt’s signing of Executive Order 9066 and the forceful removal of over 110,000 people of Japanese descent, two thirds of whom were American-born citizens.

Some evacuees were given only a few days to pack what they could carry and leave their homes and businesses for an unknown destination and an unknown amount of time. Nursery owners frantically tried to find buyers or caretakers for their businesses. They lost substantial amounts of money as they sold greenhouses, equipment, and land at staggeringly low prices. Many flower growers who wanted to keep their businesses were forced to enter into bad contracts and leased their nurseries to untrustworthy caretakers. Oftentimes these caretakers would neglect their obligations, leaving the nurseries in disrepair, crops unsalvageable, and equipment and personal property missing.

Rebuilding

Japanese detainees began returning to their homes on the West Coast when the internment camps were closed at the end of the war. Many returned to find their property vandalized or missing. Overall the East Bay flower growers lost millions of dollars because of evacuation, the exact totals probably never known. However, many nurseries did survive internment because of the generous efforts of non-Japanese neighbors, friends, and fellow nursery owners that maintained the nurseries for the Japanese growers while they were interned.

For the flower growers of the East Bay the future looked bleak but not impossible. The fact that 75 percent of Japanese flower growers owned their property before the war was a huge advantage over other businesses. Most also had houses on their nursery properties and did not have to find new places to live once they returned. The growers were also returning to a market that had felt their absence and the demand for flowers was greatly exceeding the supply. But the flower growers faced plenty of obstacles in reestablishing their businesses: Damaged greenhouses and equipment had to be rebuilt or replaced; nurseries had not been restocked with plants and were, therefore, not profitable until stocks were built back up; and there was the lack of reliable labor.

The nursery owners were all Issei (first generation immigrants, most of whom were in their 50s or older by the time the war was over. The period of reestablishment was a time of rebuilding in a new market as well as a time when the industry’s reigns were gradually being passed to the American-born Nisei generation.

Under Nisei management, the flower business successfully recovered after the war. Advances in shipping, greenhouse technology, and floriculture techniques contributed to the industry’s success and aided in continued expansion and the Bay Area remained a major center. Alameda County alone had 10.11 million square feet of greenhouses in 1980.

End of an Era

It was not until the 1980s that the once booming Bay Area flower industry began to gradually wilt. As the population grew and suburban housing began its sprawl the nurseries once on the outskirts of cities became unwanted neighbors in the middle of suburban communities. The land was more valuable as home sites than greenhouses. To escape the many problems of operating in highly populated areas, flower growers began moving south, as far as the Monterey Peninsula, and the Bay Area eventually lost its position as the focal point of Northern California floriculture.

The Bay Area and California flower industry faced an even worse problem in 1991 with the passage of the Andean Trade Preference Act. As part of its “war on drugs” the U.S.government attempted to reduce the amount of cocaine produced in South America by encouraging Colombian, Peruvian, Bolivian and Ecuadorian farmers to replace cocaine with flowers–and to import them to the U.S. tariff free. The South American growers, already at an advantage with lower labor costs and operation costs, and with the perfect climate for growing roses, could now export to America free of charge. Domestic flower growers could not compete with the bigger, cheaper South American flowers.

Northern California nurseries began rapidly closing and by 1995 greenhouse footage in Alameda County had dropped to 1.95 million with only 30 or 35 nurseries still in operation. In 2009 only a little over one million square feet were under glass in Alameda County. Today the few remaining Japanese growers have relocated to Gilroy, Monterey and other coastal areas south of the Bay. Only two Japanese vendors remain at the San Francisco Flower Market.

Although the heyday of Bay Area flower production is over, the contributions of Japanese flower growers have left the industry an enduring legacy. Their innovative spirit, determination, and hard work helped shape and establish an industry that continues to grow and evolve. And most importantly these immigrant flower growers planted roots from which a strong and vibrant Japanese American community continues to flourish today.